Navigating 'Failure to Thrive': A Mother's Journey Through Diagnosis and Decision-Making

A story about the power of diagnostic language and informed decision-making in the management of complex and rare disease

Alden’s 1st bday (before surgery)

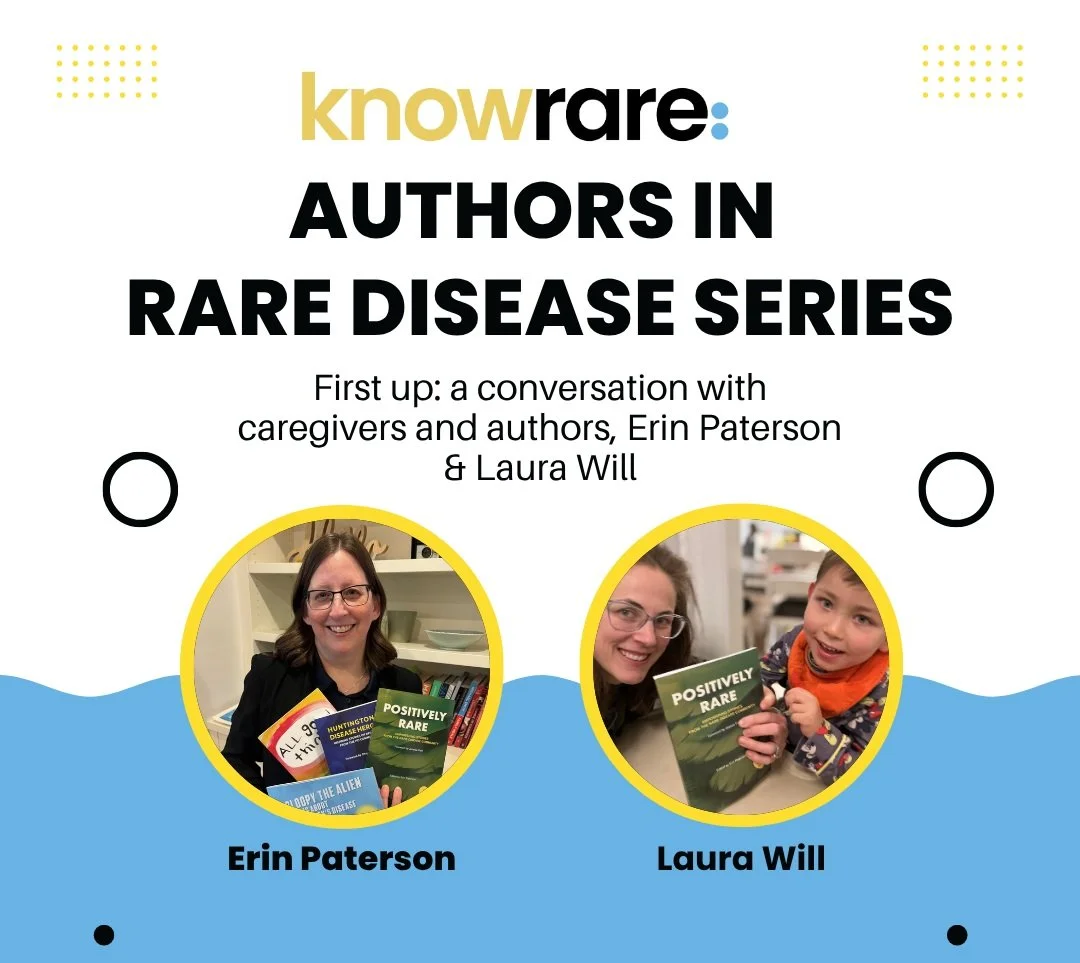

By Laura Will

I can recall the sunny, white-walled classroom, on the upper west side of New York City, where I first heard the medical term, “Failure to thrive.” I was a student, working towards a Master’s Degree in Nursing, reviewing diagnostic criteria of various gastrointestinal conditions. Failure to thrive: a failure to meet nutritional needs due to poor intake, metabolic issues, or other underlying conditions. I remember the professor pausing, after defining ‘failure to thrive’ and its potential causes, to say something like, “What a terribly named diagnosis.” This offhand comment has stayed with me. Both the label of a diagnosis and the language of a clinician wield power within the patient.

When I entered the workforce as a geriatric palliative care clinician, I sometimes found myself documenting this diagnosis on my most complex and frail patients; but I was careful not to use the words “failure to thrive” with a patient or caregiver. To fail to thrive implies so much more than the inappropriate weight gain (or weight loss) it is supposed to describe. I became well practiced in thoughtful language around this difficult diagnosis, while also appreciating all it captured. My elderly patients with failure to thrive did in fact seem to be doing just that. Their overall fatigue and frailty often suggested more than just a nutritional issue. In clothing that hung too loosely, these patients, waning and waning, were phantoms of their former selves.

Then, I became a mom to a medically complex child; and his weight flatlined at ten months of age. He was seventeen pounds every time he was weighed, month after month. Each new specialist put him on the baby scale; and he would lay there looking up at me, weighing seventeen pounds. Despite my hours of daily devotion to trying to feed him, his underlying neurological condition made swallowing too difficult to coordinate effectively. Failure to thrive was added to my child’s growing list of diagnoses; and it felt right, for both of us.

“This is what palliative care does best: decision-making where quality of life is true north.”

I was thankful to know that we had options. Our son’s rehab doctor suggested we consider surgically inserting a gastronomy tube (g-tube) so that food and water could be delivered to his stomach without relying on oral feeding. Despite his poor nutritional status and my clinical training, I was unsure what was best for my child. Additionally, with almost every medical intervention, there is inherent risk and suffering. So, I reached out to the pediatric palliative care team and we had a memorable conversation around this decision. It was strangely joyous. We centered the conversation around his well-being, and we discussed family values, my son’s unknown developmental potential, and what mealtime might look like moving forward. This is what palliative care does best: decision-making where quality of life is true north.

Alden, post-surgery (morphine snuggles)

With all we had learned and prioritized, we decided to move forward with g-tube surgery. I had to reframe my expectations of how my child would enjoy family dinners. I had to let go of the concept that I could do this alone. About two weeks later, I carried him into the surgical suite hoping this was the right decision, and watched his seventeen-pound body go limp with anesthesia. I held him as he woke, confused and screaming in postoperative pain. The nurse tried to console him with a binky dipped in sugar water; but ultimately, he received IV morphine and once again went limp in my arms. It was awful; and yet, I had been as prepared, as much as possible, for this through the process of informed consent decision-making with the palliative care and surgical teams. Thirty-six hours later we were discharged home with tubing, formula, and instructions on post-surgical care. It was January, 2021.

Rarely in medicine can we look back at one treatment decision, and see unilaterally good outcomes. My now toddler has been gaining weight steadily from less than the first percentile to almost the tenth percentile on the growth curve. With his formula food slowly pumping into his belly, he plays with his puréed foods at family meal times with no pressure to perform. It’s fun for everyone and routinely leads to extra loads of laundry. That being said, he vomits routinely from reflux and his g-tube stoma insertion site gets rashes occasionally and is always sensitive to the touch; these were known risks. He looks uncomfortable and occasionally cries when we clean it quickly twice a day. We do what we can to mitigate this ongoing pain.

Alden at school, Oct 2022

A week ago, in October 2022, my son’s gastroenterology doctor casually turned to me at the end of our most recent routine appointment and said, “I’m officially taking ‘Failure to thrive’ off his diagnostic list.” To my surprise, a diagnostic burden that I did not realize I still held on to finally dropped away. It had been almost exactly two years since my son first weighed in at seventeen pounds. In that time, my son and I have been fighting failure. We have been learning to survive; and, we have renovated the definitions of what it is to thrive. We now thrive within the confounds of our conditions - he as a medically complex child, and me as his mother.

As patients and clinicians, there is power in a diagnosis, in the language we use, and in the informed decision-making process. We need to discuss the nuances of a diagnosis and the risk of benefit and the risk of harm of any treatment. The conversation must include the values of the patient and family and the expectations for quality of life. This is the best we can do at every turn in the treatment odyssey of rare and complex diseases.

Failure to Thrive, a poem

(By Laura Will, written just after the surgical consult)

For a while now, we have noticed

the inky dots that doctors track

flat lining

Despite all

the mashing and blending

straining and scooping

of each fortified culinary creation

even with a team of specialists

thousands of breastfeeds

and tens of thousands of spoonfuls

in spite of all those successful swallows,

we are here

for a surgical consult

contemplating the weight of you

as horizontal black dots

lead onwards, but not upwards.

We are surviving.

About Rare Resiliency:

Rare Resiliency is a monthly column written and/or curated by Laura Will. This column explores the concepts and skills that play a protective role against chronic and acute stress. Each article challenges and encourages the reader to continue to develop that inner steadying strength as they face illness and uncertainty, sorrow and joy.

Besides being a mom, wife, daughter, sister and more, Laura Will is also an important member of the Know Rare team, helping and leading the review of clinical trial inclusion and exclusion information to support our Patient Advocates and their conversations with patients inquiring about clinical trials.